13. 11. 2014.

Driven by the vision of work-based society, the government has set about re-industrialising the country. I am convinced that the concept is entirely flawed. Leaving the analysis of short-term effects to others, I will explore the challenges faced by economic policy makers over the coming decades. Not only in Hungary, but the world over. Forced industrialisation is certainly not going to help us. In the past one or two years, leading tech companies such as Apple and Amazon have spent billions of dollars on researching robots. Google has acquired close to a dozen companies dealing with robotics. This keen interest is due to the fact that in terms of the development of robots, we are where we were with computers 35 years ago. Their price is falling sharply, while their potential field of application is becoming broader. A prototype has already been produced for a general-purpose robot, which has not been manufactured and pre-programmed for the execution of a specific task. On the contrary, “general purpose” means that the robot is able to watch and imitate, and thereby to learn a variety of simple work processes that have not been pre-programmed. It is called Baxter and costs 22,000 dollars. It is in fact not very expensive compared to the annual labor cost of a worker.

Baxter is not yet clever enough to replace factory workers requiring lower qualifications, but this will not be so for long. In a few years’ time, a general-purpose robot will be constructed that will be capable of learning versatile and complex routine tasks, and of carrying them out faster, more reliably and cheaper than humans. In such a technological environment as ours, setting a country to assembly tasks under the auspices of industrialisation is like styling the manufacture of board games as a leading industry in 1980. At that point, the big money should have been invested in education, the training of programmers and engineers, and knowledge-intensive areas—and that remains the case to this day.

Transforming transportation

Speaking of Google, the company’s self-driving cars have been roaming the roads of California and Nevada for years in the test phase. Today, they travel much safer than they would if they were driven by humans. When mass-produced, they will also be considerably cheaper. First, it is probably trucks where installing driverless technology will make sense, allowing forwarding companies to save heaps of money. Unpaid wages, fewer accidents, lower insurance costs, and time gained in continuous operations all mean savings to them.

Buses and passenger cars are next. Who will call a human-driven taxi when a driverless cab is cheaper and safer? For a while, many people will be suspicious of driverless cars, but this will pass quickly. Driving taxis and trucks as a profession will disappear. Around the world, the forwarding industry employs tens of millions, perhaps a hundred million people, whose work will no longer be needed. This is not the question—the question is when.

Redundant activities, redundant people

In such a world, keeping a car will become unnecessary for a lot of people. Indeed, generally we make use of our cars in a very small percentage of the time, it is mostly parked somewhere. It will be much cheaper to rent a self-driving car for that short time. It will come to my address if I book it on the web, and will go on its round to collect the next passenger once I have got out. Overall, it will cost a fragment of ownership. That is, much fewer cars will be needed, which will hurt car manufacturers and their workers.

The list could go on and on about fields where routine tasks requiring low qualifications will be taken over from humans by robots. A much smaller number of warehousemen, fast food restaurant staff or shop assistants will be needed—it is their jobs, among others, that are at risk in the first place. And it is highly doubtful that they can find other work to do.

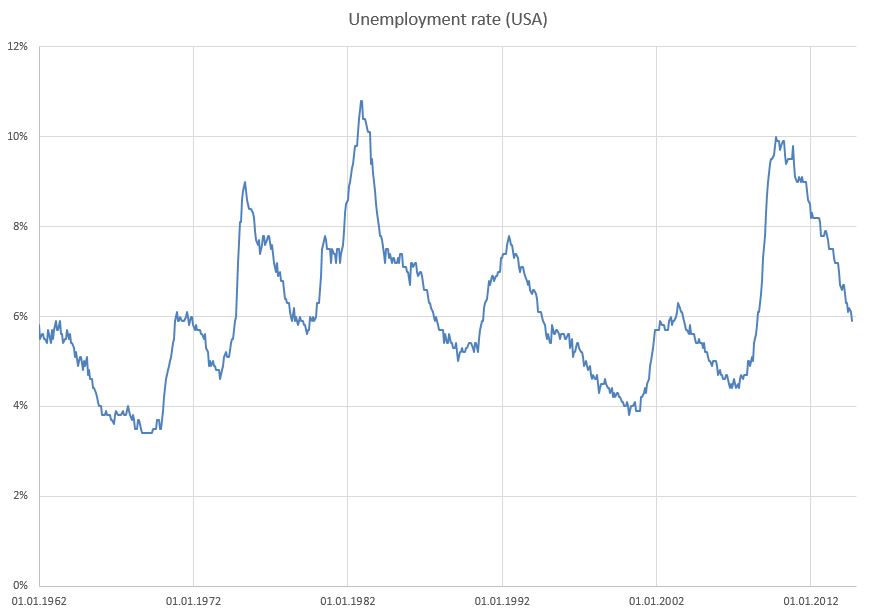

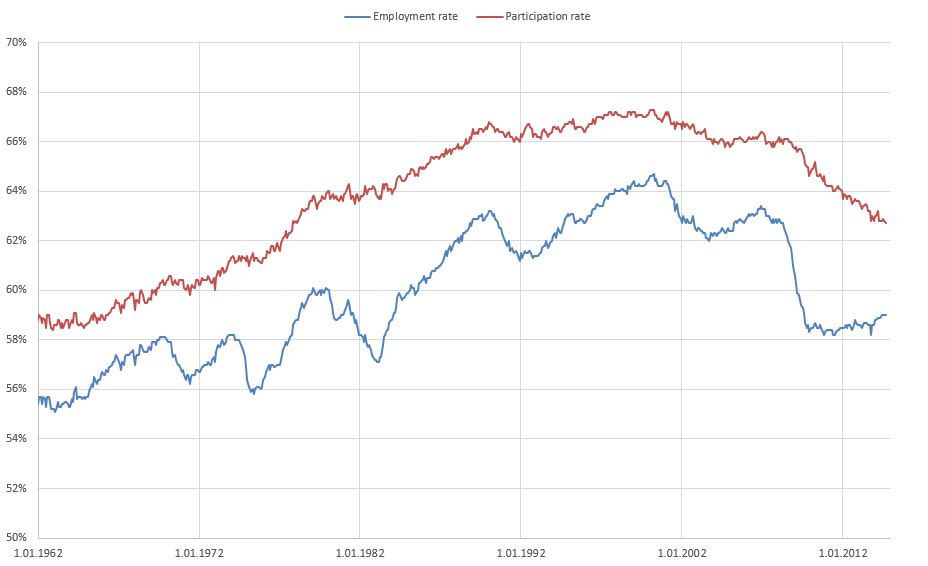

Labor market developments

Declining activity

The figure shows the dramatic impact of the crisis of 2008–2009 on the US labor market, causing the employment rate to fall sharply. However, recovery from recession looks completely different compared to previous cases. There is hardly any rise in employment, and the narrowing gap between the two curves (i.e. the fall in unemployment) is mostly due to a steep decline in the activity rate. This means that fewer people want to work while the number of people with jobs is approximately constant. The trend is partly independent of the crisis and fits into a longer-term process.

The trend of the activity rate saw a change around the turn of the millennium. The decelerating growth characteristic of the period until that time turned into an accelerating decline. This is not due to demographics; a similar process is taking place in the population aged 25–54. The explanation to the phenomenon is complex, one significant effect being that young people are starting work at a later age. In turn, the reason for postponed entry to the labor market is the decrease in the number of jobs requiring low qualifications. Before someone starts work, they are required to spend more time studying, as a result of which an increasingly wide group of people in education are absent from the labor market.

Lost jobs

Therefore, in the US labor market the decrease in the number of jobs requiring low skills is apparent even today. While this obviously includes the effect of production facilities relocated to China and other countries offering cheap labor, that does not make a great difference, and the trend will only become stronger. What should we do about this process? Education helps, but many will not be able to make it to graduation. On the other hand, a number of professions requiring special skills also involve enormous amounts of routine tasks. Accounting is complex yet almost exclusively routine work, which software will soon be able to learn and master by observing the work of an army of real accountants. After that, it will do better than anyone.

The same applies to professions requiring advanced lexical knowledge. Medical science consists of an enormous amount of information, which no physician can remember in its entirety—and they cannot be expected to do so. This, however, results in a plethora of misdiagnosed cases. Based on the description provided by the patient, findings, medical history, and medication taken, as well as on a statistical comparison with similar cases, adequate software will be capable of giving a better diagnosis than doctors. What is more, it will keep learning; and not only from its own cases, but also from all the other cases of software running in the rest of the hospitals. And it will not forget.

Lawyers are required to be familiar with tens of thousands of pages of continuously changing legislation. During their work, they are required to read, understand and process a huge amount of documents, which takes up a good part of their time. This aspect of their work will soon be taken over by robots.

Such software solutions are currently being developed, and are not in the inception phase. As they become increasingly sophisticated and reach a certain level of quality, they can get to work right away. In the services provided by them, the quality available to the broad public of average users will only improve, which is a welcome development. As a result of such innovations, however, much fewer professionals will be needed than would be otherwise.

Unconditional basic income?

Thus, on a horizon of decades, many people look set to be left out of work through no fault of their own. They will have no hope of ever getting a chance to start work. The unemployment rate could soar to several tens of percent. What should we do about them, what should they live on? We could grant them an unemployment allowance, but given the general social nature of the problem, it would be unjust if its amount was sufficient for mere subsistence. On the other hand, it would be an absurd world where machines are capable of performing infinitely efficient and cheap work, but a major part of humanity cannot afford this and lives in poverty. The unemployment allowance therefore needs to provide a decent living.

In this case, many people would not work to become eligible for the allowance. To avoid that, the solution could be to ensure that everyone gets the money for a decent living, irrespective of whether they work or not. But then the money is no longer called an allowance—it is unconditional basic income.

Of course, everything may fall out otherwise. The jobs lost may be replaced by new ones. Or they will not, but instead of a basic income, unemployment-based society will try to solve its problems by completely different means. However it will be, we will continue our mental experiment.

Next in the series: Life in an unemployment-based society

Related posts: